Irish Times editorials often characterise the Irish public as angry and irrational, responding emotionally to economic and political crises instead of pragmatically.

I initially wanted to write a post titled ‘The Dáil Gazette, or as its commonly known the Irish Times‘ looking generally at the how the Times’ opinion pages are so often adorned with analyses and editorials that seem to have been lifted from the crib notes to a speech at the Fianna Fáil tag-rugby club awards evening, for instance:

“THE FIANNA Fáil leadership issue will now be brought to a conclusion. Brian Cowen put it up to his critics, particularly Micheál Martin, to put or shut up.”

“The Taoiseach played a blinder in his press conference after a 48-hour consultation period with his parliamentary party last evening.”

“His message was courageous, open and democratic.”

“He hit the right note by stating that his decision to stay on as Taoiseach was in the interests of the country, not the party.” [Fianna Fáil convulsions 17/1/11]

But more specifically, I wanted to find out whether the Times’ seemingly populist calls for an early election were always immediately followed by various justifications for a delay of that necessity. For example, here is the Irish Times in December 2010 calling out for a general election:

“THE NEED for a general election at the earliest possible opportunity has increased, rather than diminished, in the aftermath of the Budget. There should be no question of a long, drawn-out debate on the Finance Bill in the New Year or waiting until special legislation on climate change or corporate donations has been adopted. The sooner the electorate is given an opportunity to shape the political future of this State, the better. We are at debt’s door and it is simply not good enough to revert to party politics.” [Election required as soon as possible, 10/12/10]

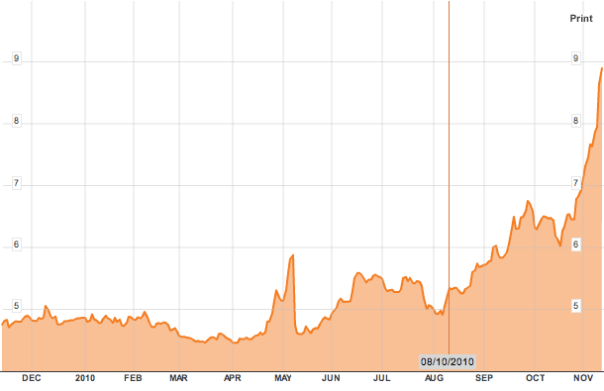

“THE SOONER a general election is called the better. Public approval for the way the State is being run has shrunk to 8 per cent while the level of dissatisfaction with the Government has ballooned to a staggering 90 per cent. Taoiseach Brian Cowen’s approval rating has shrunk to an all-time low of 14 per cent while, taken together, the Coalition parties now command a shrinking support base of 19 per cent. Such a comprehensive rejection of policies, personalities and parties should not be ignored.” [Volatile movements, 16/12/10]

However, before we get around to the difficult business of elections, there is a pressing issue at hand – a very good reason why an urgently needed election must be postponed just a little bit longer. If it’s not NAMA, or various bank nationalisations, or negotiations with the ECB and IMF, or emergency budgets etc, its the Finance Bill:

“This amounts to an unwillingness to face the electorate. Only one piece of legislation is required before the Dáil is dissolved and that is the Finance Bill. It could be enacted quickly if the political will exists.” [Edging towards a general election, 8/1/11]

“As political events unfold, it might be in the national interest for Fine Gael and Labour to agree that they would guillotine the Finance Bill through the Dáil and Seanad – if their primary aim is to have a general election as soon as possible.” [Fianna Fáil convulsions, 17/1/11]

“The Opposition parties should guillotine the passage of the Finance Bill and bring on the election.” [They are where they are now, 19/1/11]

But, trawling through the archives I was distracted by a phrase that kept popping up – ‘the angry electorate’:

“Brian Cowen will lead on. The general election may be deferred until March. But the outlook for the Government parties is so bleak that only a miracle can save them from the anger of the electorate.” [‘Looking towards a fresh start‘ 27/12/10]

The angry electorate is everywhere in the opinion pages of the Times, especially in the editorials.

“The anger and volatility of the electorate has been revealed in the latest Irish Time /Ipsos MRBI opinion poll that also shows an unprecedented shift of support between the Opposition parties as uncertainty grows about the composition and policies of the next government. The findings reflect the political turmoil that beset the State as the Government sought a financial bailout from the International Monetary Fund and the European Union; published a four-year economic plan and introduced an unpopular Budget that broadened the tax base and cut welfare payments.” [Volatile movements 16/12/10]

“The public has become angry and frustrated by the incompetence of the Government and the apparent insulation of many Oireachtas members from the realities of the daily grind.” [Facing up to the realities, 28/10/10]

“The frenzied reaction of the media was not pretty to behold but did reflect the level of anger that exists among an electorate shocked and bewildered at what is happening to the country – and the seeming inability of the Government to get to grips with it.” [Traumatised electorate deserves a leader at the top of his game, 16/09/10]

“For more than a year now, I have spent most of my working weeks mixing with people from many parts of Ireland. I have had time to gauge the public mood. There is deep anger and a feeling of helplessness; a fear of the future and a profound sense of betrayal. There is, to a worrying degree, disillusionment with the whole political system.” [FF and Greens must bow out while sanity still prevails, 13/1/11]

“Nobody has been held accountable for the damage done to the State. Public anger is palpable. Structural, indeed moral, reforms are needed.” [Holding banks to account, 15/12/10]

“At this stage, the public is so angry and disillusioned by economic mismanagement and the shenanigans of government ministers that it doesn’t really care who leads Fianna Fáil […] The anger out there is palpable.” [They are where they are now, 19/1/11]

In the last two cases, ‘the anger out there is palpable’ and ‘public anger is palpable’, it sounds as if the editor, or whoever was tasked with writing the editorial, imagines themselves trapped inside the Dáil along with the elected officials, attempting to save or salvage the country’s economy while the hounds of public opinion attempt to ram the gates with a cement truck.

This ‘anger’ is used as a unsubtle means of implying the public simply doesn’t understand economic realities. It is predicated on the assumption that the public is inherently irrational, that the reason for their disapproval of various measures, such as austerity budgets, bank guarantees and bailouts, is down to the fact they simply don’t understand there, is, no, alternative:

“[In Argentina] The failure to navigate between an angry public and the fiscal constraints of IMF conditionality cut short a dozen careers in the Argentina finance ministry in the last decade. Is this the future that awaits a potential Fine Gael-Labour coalition?” [Next government must be able to take decisions, 6/12/10]

“Growing and understandable public anger, coupled with extreme economic events, has prompted the political system to table a range of policy and legislative changes that could only be described as a mixed bag. Some measures, such as those aimed at reducing the cost of doing business and the broadening of the tax base, are sensible and long overdue. Others though are ill-advised, populist or poorly thought-out and will stifle economic regeneration.” [Danny McCoy (IBEC) and Paul Sweeney (ICTU) head-to-head, 31/12/10]

“From conversations with Opposition figures, I know they are genuinely angry at Government failures, and believe strongly it should be replaced. But I also sense a genuine desire to do what is right for the country.” [Strategy for tackling deficit widely seen as incomplete, 28/09/10]

That anger is a euphemism for the public’s perceived irrationality is demonstrated by those instances where it is mitigated with words like ‘justifiable’, ‘understandable’ or ‘righteous’:

“President Mary McAleese said the crisis engulfing Ireland “obliged” us to “to take a step back” and discuss the country’s future. Ireland needs to channel the “righteous anger” people are feeling into national debate” [Ireland needs a national forum for cogent debate, 26/10/10]

The ‘angry electorate’ is such a staple phrase of political reporting that journalists even make joking references to it:

“I think journalists’ fondness for public office, which usually strikes the journalists concerned in late middle age – hey, I am so there – comes from our communal conviction that we are running the country already. We shout about the state of the nation quite a lot when we’re on the phone to each other. We laugh knowingly. We curse and swear. We do a little bit of swaggering at our keyboards. Because we know the score. Politicians are idiots. These conversations constitute our political experience, and qualify us to dash out looking for a nomination, a book deal or a chance to address the angry horde and give it the benefit of our opinion.” [Being a TD could add up to being the perfect job, 17/1/11]

Politicians, on the other hand, can be seen showing the public how it should be done:

“IT SAYS something for the shell-shocked state of our politicians that yesterday’s Budget, certainly the most savage in living memory, was spelled out to a Dáil chamber that, for the most part, was resigned and subdued rather than angry and boisterous. The public was waiting for the hit that will determine their living standards, not just for Christmas but for the next couple of years or so. At least there is some certainty about the expectations we can have about our living standards now.” [Everybody takes a hit, 8/12/10]

‘Resignation’ is the proper, logical, adult reaction to necessary budgetary ‘tightening’ and tax base ‘broadening’. A sentiment hammered home in the headline, ‘Everyone takes a hit’.

There is also the inbuilt idea, that the public is tempestuous, or perhaps even childish, that they simply want to vent their frustration by voting for a different party or leader:

“The only argument for Cowen remaining on is that he would act as a lightning rod for all the pent-up anger felt by the electorate at the country’s plight. Once the voters have vented their frustrations on Cowen in an election, a new leader might be able to pick up the pieces and rebuild the party.” [Sharp decision on Cowen will return focus to election, 15/1/11]

“They have had time to reflect over the break. They have spent more time with their constituents and come face to face again with the extent of public anger at the party. They have also come to appreciate the extent to which that anger is focused, somewhat unfairly, on Brian Cowen in particular.” [Senior Fianna Fáilers hold fate of party in their hands, 15/1/11]

“An increasingly angry electorate has already demonstrated its determination to punish the junior Coalition partner with a severity that has shocked the Green base. The party went into the 2009 local elections with 15 city and county councillors and emerged with just three, making it practically impossible to keep Green issues anywhere near the top of local government’s agenda.” [Besieged Greens focus on electoral survival, 16/09/10]

And if this anger is not adequately “navigated” by politicians and journalists alike, it can lead to the masses being swayed by “crackpots”:

“In short, they are mostly realists because they have always had to be. But at times like this, they too can be swayed by crackpots offering easy solutions, particularly if these appear to be finding some echo amongst the elites.

The Irish public is being urged to “dismantle the power structures”, “take back the nation”, and “reclaim the Republic” by people who, given half a chance, would reduce the country to a perpetually bankrupt, pariah state. For just a start, they would default on international loans; leave the EU; and set about creating some pseudo-Marxist dystopia (a North Korea without the military hardware, a Cuba without the sun).” [FF and Greens must bow out while sanity still prevails, 13/1/11]

A potential that was clearly evident in the Lisbon Treaty referendum, where the public allowed the ‘crackpots’ to trick them into voting the wrong way:

“The potential of this dynamic, deeply angry at a political establishment perceived as out-of-touch, has already found expression in the two Lisbon referendums.” [I’m putting my money on a new political movement, 15/12/10]

It’s very easy for journalists to dismiss the public as angry and irrational, in fact, in a lot of ways, it is fundamental to what they do.