“The media…is by far the most powerful agency in shaping people’s perspectives on social and political issues” [Vincent Browne, Irish Times, 18/04/12]

Discussing the highly concentrated ownership of Irish media on the eve of Gavin O’Reilly’s departure from Independent News & Media, Vincent Browne makes a statement his former editor Geraldine Kennedy would be proud of. Yet gone are the days when the Irish Times could credibly boast to be ‘leaders’ or ‘shapers’ of public opinion, save for a small subset of influential south Dubliners.

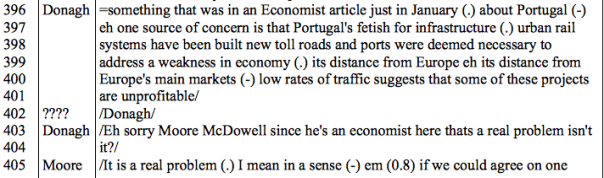

Successive campaign failures over the last few years, including the Lisbon Treaty and more recently the household charge, have shown the limitations of the media’s agency to sway public perspective. On the other hand, the media’s ability to influence or at least reinforce government thinking on certain important policy issues has not been undermined. Successful campaign wishes for austerity budgets since 2008 have been granted, with politicians responding to the media “call to arms” by throwing caution to the wind, “sticking to their guns” and delivering the required “tough medicine” over and over.

This dynamic makes the case of the household charge “fiasco” all the more interesting. Here again the media and government collaborated in a campaign, this time for a new tax. Which, three weeks since its introduction, only 900,000 have registered to pay, from a total of 1.7 million liable. A lacklustre result you might say, but not one that’s completely spin resistant. The Irish Times made the sensible point:

“the campaign [for] modest household charge has been a fiasco. yet about half those liable have paid up”.

Although this glass-half-full enthusiasm can’t completely disguise the campaign’s “abject failure”. It’s fair to say the public were decidedly un-shaped.

While this campaign was clearly a joint government-media effort, the responsibility for failure to shape public opinion has since been laid squarely at the door of the Fine Gael-Labour coalition. The Irish Times, the Irish Independent and the Irish Examiner all rounded on the ministers responsible, questioning the “technical weakness” of the policy implementation and decrying a plan “marred by confusion and incompetence” which resulted in “sloppy injustice”. The “inept” handling revealed “systemic incompetence”, leaving “[h]uge swathes of the population simply hav[ing] no idea how to go about paying the charge, even if they wanted to”.

The Irish Examiner’s Mary Regan called it a “fiasco that left close to a million households un-registered for the charge.” Causing an Irish Times editorial writer to worry that “nobody in Government appears very concerned at the way its policy looks like going down in flames.”

Politicians could well be forgiven for thinking they got a raw deal. The media, according to the knowledgeable Browne, is the “most powerful agency in shaping people’s perspectives on social and political issues”. Yet even on this issue, one it fiercely campaigned for, it refuses to acknowledge its share of the blame for this “serious embarrassment”. It is as if it is oblivious to its own agency, except of course where the result is welcome.

A further interesting aspect to the mass household charge avoidance is the various narratives that have been created around it, to justify it and to explain it’s non-payment. Almost all of these narratives side step the context of 4 years of austerity, a number of “courageously masochistic” budgets, mass unemployment and renewed emigration. They have instead attempted to frame the tax as a historical anomaly which needed to be rectified. And it’s failure as a) an inadequate policy implementation or b) a cultural and historical deviance unique to Ireland. The equitability of the tax itself is considered primarily in the context of what scale the charge should be as opposed whether it should be introduced at all, i.e. complete acquiescence to the ECB / IMF plan. At a fundamental level the media and the political establishment are on the same page, dissent in this context is simply strategic.

Politically speaking, the PR narrative of the household charge was carefully developed in line with this consensus. In the beginning it stressed the historical requirement for charge, while perhaps chiding the unfairness of the €100 blanket amount and when the whole thing went belly up it dismissed the widespread avoidance as non-politically motivated, a simple failure to read the instructions properly. There is of course an important reason why this narrative is preferred, there’s a very real fear that this scale of avoidance could turn theoretical fears of austerity beginning to buckle into cold reality.

So reporting reflected this need to slow “traction” of the “message that austerity isn’t working”, because a “failure to collect the tax could send out a message that the fiscal austerity programme is starting to slip“. An unacceptable eventuality when there is only one economic recovery game in town. As the Irish Independent’s James Downey explains: “Our masters are emphatically right about one thing. We have to accept the austerity programme.” Which is the sort of “unbiased clarity” PR man Paul Allen was presumably calling for in his Irish Independent critique of what he sees as the media’s inclination for “emotionally driven reaction” to the crisis.

Meanwhile the media were simultaneously citing the absence of protest as evidence of silent acquiescence to the austerity programme and at the same time the presence of protest as a kind of infantilism, acted out by an ‘irrational electorate‘ against a “petty target“.

Stephen O’Byrnes blamed “[a] kind of victimhood or entitlement culture [that] has gone unchallenged by too many media outlets.”

An Irish Independent editorial writer called it “nothing more than another manifestation of our ongoing culture of civic irresponsibility.”

Breda O’Brien dusted off a copy of Freud and told us: “People feel hopeless and fatalistic and, therefore, refusing to pay something such as the household charge feels positive and good. In reality it is a distraction from far more important issues.”

Presumably the same issues Stephen Collins was referring to when he began campaigning for a Yes vote in the referendum on the European Stability Treaty back in February – “[the household charge will] obscure the real issues”. To put it bluntly, as only the Irish Examiner’s Jim Power can, “It is time people copped on to the realities.” Echoing Justice Minister Alan Shatter’s considered advice to the country a day earlier – “get a life“.

Those who supported the protests were, invariably, little more than “disingenuous” “opportunists” exploiting the issue as a “ticket for their re-election”. Their “left-wing outrage” was standing in the way of an “act of social progress”, with fringe politicians “pursu[ing] power at the expense of responsibility”. According to Matt Cooper opposition figures were just “overjoyed that they have an opportunity for major protest.” This “self-serving hypocrisy”, we were told, “expos[ed] the shallowness and self-destructive nature of Irish politics.” While the Irish Independent warned those drawn in by this “selfish individualism” that “they shouldn’t complain if after lying down with mongrels they wake with fleas.”

The contrast between these dissenting left wing politicians and those who have “develop[ed] the new level of maturity” required for governing couldn’t be more stark. As Brendan Keenan explains: “If anyone can sell the public austerity it’s Michael D”.

The “worrying” thing is, a poll on voting intentions carried out last week indicated a fairly dramatic swing in preferences from the main political parties to independents and minor parties. The Irish Times was especially incensed, it’s editorial headline read, “A pattern of alienation”, before the writer went on to explain the public’s “growing disillusionment” in the patronizing manner you come to enjoy as an Irish Times reader.

The protests themselves were not-nearly-large-enough in scale, failing to impress Dan Hayden and Colin Scott, the Irish Times’ experts on how to get people to pay tax. Yet that’s not to say they didn’t generate some column inches. The Irish Independent was especially excited, with at least one journalist seemingly mistaking Galway for Homs or Benghazi. At the Labour Party’s annual event just over a week ago an “angry mob…stormed Garda barricades”.

John Drennan described how only a “thin blue line” stood between the conference delegates and the protesters. The Gardai were forced to use pepper spray “to hold the crowd back“, with some journalists caught “in the crossfire”. At another protest demonstrators “attempted to attack” Environment Minister Phil Hogan’s car, mercifully the Minister “did not appear to be in any danger.”

These protesters had clearly misunderstood the Irish Independent’s headline advice in late 2011 – “This is not a time for timidity“. On the contrary, to be “courageous, radical and imaginative”, as the Irish Times explains, is to “stick resolutely to the path of fiscal consolidation“.

Which brings us to the reasons why people chose not to pay the charge. If it wasn’t the “the Government’s astounding incompetence in the household charge affair“, it was something deeper. A cultural explanation for a uniquely Irish problem, much like our “unique love-affair with property”, which as it turns out isn’t that unique at all.

The Irish Examiner’s Fergus Finley was “absolutely convinced” he had identified the true reason, concluding that “it would be a mistake to assume that the reason people didn’t pay was ideological, philosophical, or political. It was cultural.” While other papers variously flip-flopped between the “technical weakness” explanation – the “methods of payment” were “unnecessarily complicated” – and the historical anomaly explanation – “people…are horrified at the notion of paying a property tax in any guise”. A revelation many of those who paid exorbitant stamp duty charges during the bubble years can no doubt sympathize with.

Other commentators simply cited relevant economic equivalences: “Every other European country has property and service charges. Why should this State be different?” and “The reality is that Ireland is one of the few countries in the developed world where some form of residential tax is not paid.” A compelling logic that it is rarely made with respect to Ireland’s corporate tax rate.

This kind of obfuscation sought only to disguise the reality that the charge is firmly embedded in the austerity programme. Not only is it a requirement of the ‘bailout’ ‘agreement’, it is part of the political and economic orthodoxy that has secured power post-2008. The ‘general unfairness’ of the austerity programme features in a number of columns, however what is placed between is for the most part entirely consistent with government and ECB / IMF policy. These empathic book ends are little more than sugar to help the “tough medicine” go down.

The household charge is fundamentally a condition of ECB / IMF monetary lending, just like the universal social charge, just like the repayment of Anglo’s debts and just like the closing of hospital wards. A widespread refusal to pay the charge represents a problem for the establishment. This is clearly not the impression the government and it’s ECB / IMF partners want to send to ‘the market’. Austerity, according to the ECB, is Plan A to Z, there are no other options.

One of the few places where you can read this kind of honesty is the business pages, a space less tolerant of political spin. The Irish Independent’s Donal O’Donovan cited a financial analyst’s concern that “resistance to the household charge had registered with investors abroad as a possible indicator that the perceived success of austerity here could be reaching its limit.”

The consequences are clear, if it cannot be sold to the public and adequately enforced, the house of cards of which the EU ‘bailout’ is built could come tumbling down.

The foundations are already beginning to shake. Even austerity zealots such as the Irish Times’ Dan O’Brien are beginning to express doubts as to whether the programme will work in the end: “Austerity may fail in southern Europe and Ireland”. Clearly mindful not to follow in the foot steps of his predecessor, Marc ‘The Best is Yet to Come’ Coleman.

The same sentiment has been expressed countless times over the last few years, not just by respected economists such as Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman, but by proponents of the policy themselves.

The IMF’s April World Economic Outlook stated: “Austerity alone cannot treat the economic malaise in the major advanced economies.”

The IMF’s Poul Thomsen said in January 2012 with respect to Greece: “We will have to slow down a little as far as fiscal adjustment is concerned.”

IMF economist Olivier Blanchard said in December, according to Business Insider’s layman translation: “aggressive austerity — apparently only makes the problem worse”.

And in September last year the IMF “called on the US and Europe to abandon fiscal austerity and switch to stimulus measures, warning that the global economy faces a “threatening downward spiral”.”

Perhaps like the Nobel prize winning economists and the “radical” political dissenters, the public is beginning to realize what has been abundantly clear for years now to those “47% of [Credit Union] customers [who] have about €100 left after paying their bills“, that ‘there is no alternative’ doesn’t mean there is no alternative, it means they don’t want us to imagine one. Far from being disillusioned and alienated, it’s possible the public are beginning to see more clearly.